Collegial governance must survive for universities to thrive: conference

Amid an increasingly uncertain future, the mission of universities to navigate complexity, generate collective knowledge, and support the common good is more important than ever.

But these lofty goals can’t be accomplished unless the voices of academic staff are central to university governance, panelists at a recent Confederation of University Faculty Associations British Columbia (CUFA BC) conference said.

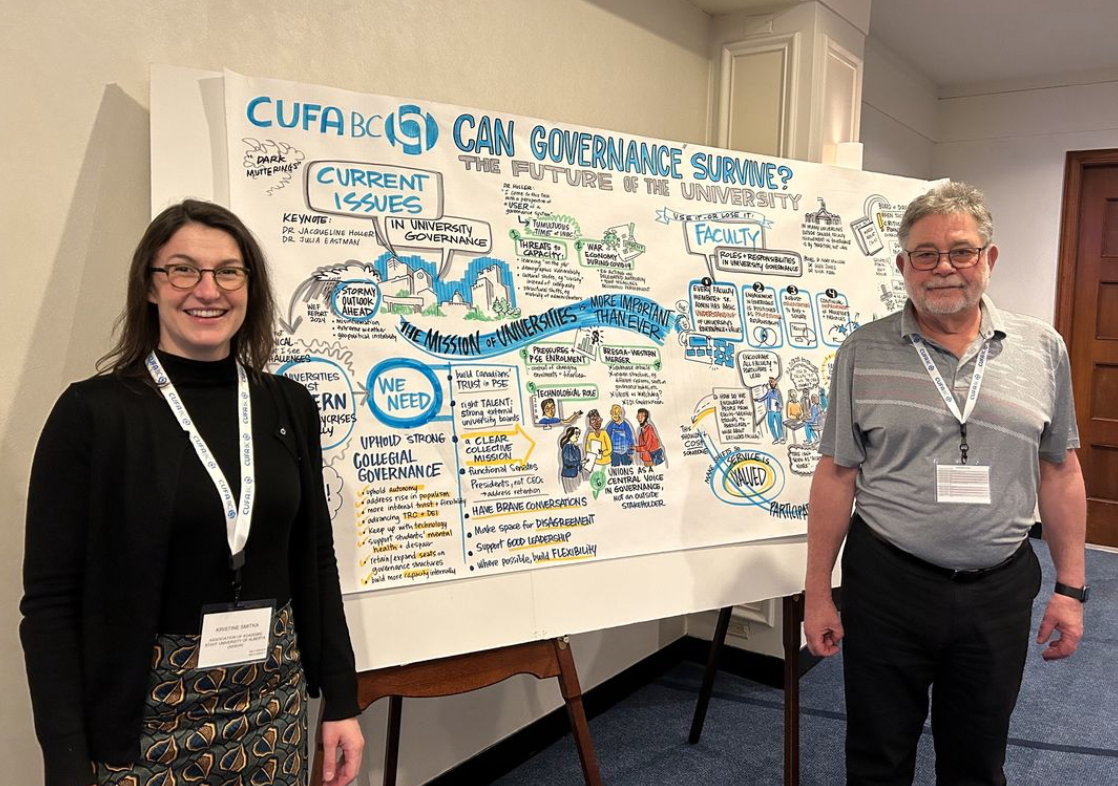

AASUA attended CUFA BC’s university governance conference which took place from January 18-19. In attendance were President Gordon Swaters, Vice-President Kristine Smitka, Executive Director Brygeda Renke, and Communications Officer Rachel Narvey. Held in Vancouver, the conference was titled ‘Can Governance Survive? The Future of the University.”

Defining collegial governance

Academic staff are not merely another university stakeholder. Instead, they are a central part of healthy post-secondary decision-making. Their voices are essential for crafting and monitoring the university’s goals; choosing and evaluating administrators; as well as creating and refining university policy.

Most Canadian universities have a bi-cameral structure: a Board of Governors makes financial decisions and a second body, known in Alberta as the General Faculties Council (GFC), is charged with directing academic affairs.

Throughout the conference, panelists referenced ‘Governance Inversion,’ a term coined by Mount Royal Computing Science Professor Marc Schroeder, to describe when a university administration limits the role of the GFC in order to accomplish the Board’s singular agenda.

Conference attendees discussed ways to bolster collegial governance given this worrying trend, which has greatly impacted the University of Alberta. Some ways forward, according to Glen Jones, a Professor of Higher Education, included:

- Positioning academic staff participation in governance as a professional responsibility, rather than just a service;

- Ensuring every academic staff member and senior administrative staff member has at least a basic understanding of the core structure and principles of their university;

- Including robust orientation programming for Boards and Senates/GFCs; and

- Creating spaces to discuss the continuous improvement of governance practices and policies

To wade in or wait it out

One theme of the conference was the role of early-career academic staff in university governance.

While some argued early-career academics should focus on establishing themselves in their work, many expressed the need to turn away from this perspective and instead encourage young academic staff to become involved.

“I really resist the idea that we have to shelter academic staff from service until they have tenure,” Shannon Dea, Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Regina, said. “They need to be developing their skills and their literacy in that duty …

“If you hit Associate Professor and decide to start engaging, you’ve already lost a lot of opportunity to not only learn about how to do it, but also to build the kind of relationships across the university that are going to help you be effective at stewarding collegial governance.”

Marc Spooner, associate professor at the University of Regina, said he often feels like he has to “run a deprogramming session” with new faculty who have been told to wait to participate in collegial governance.

“If people don’t know how collegial governance works, we shouldn’t take it away from them,” he said. “We should provide the training opportunities that are needed for them to be able to do the work and understand its importance.”

At the conference’s conclusion, attendees crowdsourced key conference takeaways, one of which was that “we need to explain governance structures at universities to all community members so that more people can participate in informed and meaningful ways.”

Sessionals … citizens?

While it might be difficult for early-career faculty to participate in collegial governance, Sarika Bose, a lecturer at the University of British Columbia, noted it’s even more challenging for those without job security to dive in to this work.

“Contract faculty aren’t even considered when it comes to their stake in the academic mission because they aren’t seen to fit in to the institution in any way,” Bose said.

She compared the marginalization of contract teaching staff in the academy to that of non-citizens in a nation-state.

“Contract faculty are never citizens, working on a visa that’s temporary, in a liminal state of belonging and not belonging,” she said.

With 53% or so of university educators in Canada untenured and earning approximately 67% the salary of their tenured colleagues, the barriers to participation in governance processes are monumental, Bose noted.

“[Unfair employment] makes it hard for contract faculty trying to make a living to put themselves forward and advocate for their own rights,” Bose said.

Fear of speaking out is very real for contract academic staff, she said. In a group discussion, conference attendees brainstormed ways to help encourage contract teaching staff to participate in governance. One solution involved uplifting those who have already stepped forward as models for others to follow.

The role of unions in preserving collegial governance

While Canadian universities are not picture-perfect examples of thriving collegial governance models, they remain a place of opportunity for academic staff to have their voices lead the way forward.

Shannon Dea, Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Regina, argued this is because Canada has retained a unionized workforce right across the country.

“[Academic staff associations] are helping to ensure that we resist the tide force of managerialism in university governance,” Dea said. “The existence of [academic staff associations] is helping to maintain a firewall against global trends away from shared governance.”

Marc Spooner, associate professor at the University of Regina, concluded with a nod to author Astra Taylor.

“True collegial governance may not exist, but we’ll miss it when it’s gone.”